I went on a government scholarship

to Mona, to do special physics–

Mona campus, yeah

–in 1965. What am I saying? 1962. I used to

teach in St Stephen's College at that time,

where I taught for an academic year and a piece.

And then I went to Jamaica. When I came back,

I was placed in QRC, Queens Royal College,

to teach physics. Mainly A-level classes,

the scholarship classes, and the form– But

they also put on a number of form one and

form other things, which was pleasant

because some of these young students,

although I only spent two years in QRC,

they remember me years back, some of them.

What year was that?

65 to 67, two years.

And how old were you?

I was born in 1940 so in 65, I would be 25 years

old, 20 something. But I never wanted to teach

in Port of Spain, l I never wanted to live in

Port of Spain. l I taught in St Stephen's and

I had a terrible passion, I wasn't interested

in teaching really, but I was interested in the

development of the area I came from. And I said,

if I'm going to have to teach because I’m on this

scholarship with a five-year contract for the

government, then I want to go south. It's either

you're sending me to Presentation College or St

Stephen's College, where I had worked. Country!

St Stephen's was the only high school that they

had in the area. All the other high schools

were in San Fernando. Boys and girls. So I had

to go to Pres, San Fernando. My brothers went

to Pres and my nephews went to Pres and my nieces

and that– My sister went to school for three years

in Bishop's in town and I said I wanted to go back

to the south. Mainly Princes Town if possible. And

they told me no– they told me listen man,

everybody bawling to go to QRC and this is

the top school in town and you don't want to do

it? I said no I want to go to Princes Town. They

must have thought I was mad. I tell them no, no,

no I want to go to Princes Town, they need me in

Princes Town or San Fernando. So they agreed in

the Ministry [of Education], after a prolonged

talk, that they will look at the question,

they will look at my case as time passed

After the first year, I was so absorbed in

the little Black children in Port of Spain,

in that school, a lot of Black

children, African and Indian,

some from Laventille and all kinds of things. I

got caught up in teaching. I tell you straight, I

didn't want to be a teacher, I didn't want

to be a teacher, that's another question.

But I said, look, if I have to teach at all,

put me in south. They say they will look at it.

After the first year, I was so absorbed, I didn't

even apply to remind them but every now and again,

it would come back in my mind. And I raised the

issue— I remember once I had exams coming up,

A-level exams in my class, the senior class in

physics, trying to get a scholarship or not.

Something happened in the lab, some piece of

equipment or something. We found out that we

didn't have some raw material that we needed for

the exam, the practical exam. So I went to the

office to tell the principal, a fella name [Ralph]

Laltoo, that, look, we have to have this material

by Monday for the exam. And he looked at me–

We were good friends because I was hard-working

and he liked me and he was married to a woman

from Princes Town who was just next door to me.

Next door to where I lived in Princes Town so we

got along quite well. He had just come back from

Canada, he had spent a year or two years there,

they had sent him in that school. So, eager with

this teaching that I didn't want to teach but I'd

get caught in it, I can't get it out of my system–

So I tell him, he looked at me, he said, Suite,

why do you have your shirt outside your pants?

I said– I laughed at him I thought we were

good friends, he's the principal and I'm a

hard-working senior teacher. He said, put your

shirt in your pants. I said, Mr. Laltoo lewwe

talk about that this evening or

tomorrow or some other time. Let

us right now get the equipment for the

class. He said, this is very important.

I said, what? He's persisting, he's not listening

to me telling him about the equipment. I tell him,

I say, you know, I put in that thing that I

didn't want to work in QRC, I want to go south

I'm going to leave the teaching if you pressing

this point. It makes no sense me saying–

I'm going to go to the Ministry, I'm going to tell

them. He took what they call—they have a phrase

for it– take front before front take you—

he gone and report me to the Ministry,

which is just next door. How Suite is improperly

dressed and he told me to fix myself and I would

not fix myself. So by about one o'clock in the

afternoon, I got a letter from the Ministry

telling me that Mr Laltoo had reported me for

insolence and persistence and badly dress and

all this kind of thing. If I do not obey his

instructions, they will have to take action.

I said, what? Good. And I wrote a letter to the

Ministry telling them– I told Laltoo the same

thing– I said yuh see right now I don't own— and

I remember the phrase Arrogant lil young Black

fool from Princes Town– I remember the phrase,

I told him I said listen I don’t have a pigeon

or a parrot on a stick and if you want to

press me, I will leave and not come back.

I would stop teaching. I could go and stay in

my mother gallery. Yes, I tell him you trying

to press me to put my shirt in my pants and

you know the history of the shirt in my pants?

My brother who is now dead, he was about

six years older than me, had gone to Mona

while I was there my last year. He had done

languages, he had in the last year of the

Spanish degree – they used to go to Mexico

to spend the vacation, the long vacs, where

they get immersed in it. Just like how the French

people would go to France and spend a whole year.

So the French degree was a four-year degree

but the Spanish degree was a three-year degree

because it was right here. Encourage them to

go and spend the two summers. He had come back

about the year before. Bought about three

shirts for me, they were called Guayabera.

These are the shirts that are short sleeve, they

could be long sleeve but the pockets are outside,

both up here and down here. Right? And I

remember he bought a white one, a pink one

and a blue one. He bought back these shirts

for me. I was so keen. Nationalism in Mexico.

Why you telling me– we don't have a dress

code. We wear all kinds of crazy things,

and put on all kinds of, feeling good. I wasn’t

no radical you know. That's the next question.

So I decided look, Winston, you have

to, you have to leave QRC. Everybody

looking at QRC as the greatest place

to teach. What? Scholarship class,

this is the top, next to the Ministry. I

didnt curse. I said I wanna go back home,

I wanna go back down south. And if alyuh

don't send me? I am prepared to leave the job,

to resign and do nothing. I was really crazy

in those days. They pushed me… So when the year

finished, that was my second year. By this

time I was so absorbed, almost to the point

that I kind of wanted to stay in town because

of the students. At least two of my students

ended up being professors in medicine in Mona.

Some of them are specialists, all kinda thing.

I used to work hard and I didn't want to

be a teacher but I worked hard. So they

agreed to give me a transfer. So I had spent

two years in QRC and they sent me to Mod Sec

in San Fernando. They had just built this

school, it was supposed to have two batches

of Common Entrance classes. One for that part of

San Fernando and one for Penal so the school was

called the San Fernando and Penal school. Years

after they built the school in Penal for them. A

number of years, it was carrying two sets of form

one. So the first year, when I went down south,

the school was about three years old and I went

down there and fell into the trap of teaching.

You know It was a passionate thing I'll

tell you. I met a number of students who

went to Pres. And we decided that we want

to make Mod Sec as it was called as good

as QRC, as San Fernando Pres. We all went to

Pres or most of us and we decided we're going

to make Mod Sec as good. And that was about

cricket, sports, football, academics. And we

started to work hard— in fact out of that by

two year’s time we got a couple of students,

I know some of them names by heart, remained

friends, retired now — A-level distinctions in

physics. I was teaching physics. And there was

a woman named Brader Lynch from St. Madeleine.

She went into health and things like that. She

did work with the medical faculty. She did her

PhD in teaching all kinda thing. But then she was

doing chemistry, she had just come out of Mona,

out of St Augustine. So I would have been in my

third year when I went to Mod Sec of the contract

and she might have been In her first year. And we

all were worked up about this Mod Sec and making

it into some, this great school blah blah blah

blah blah. Stay giving lessons in the evening for

nothing. Staying late, coming Saturday, all

kinds of things. I got trapped in teaching.

How many of you were doing that?

All the staff. Young, young men, some of them

dead. Leslie Sooklal is dead. One or two of them

migrated to Canada. But [Harold] Ramkissoon

spent a year there. He went in to UWI after

and so we went. Worked hard. And sooner or

later my brother who graduated was sent to

Mod Sec. So the two of us ended up in the

same school. Had another friend of mine,

Rawle Aimey, sportsman national footballer,

all of this, who also went to the Pres and

sort of thing. We really set our head down, we

decided that we were going to work hard and make

this school a good school, a great school,

scholarship winning, all this kind of thing.

And so I'm now in San Fernando, 65, 67.

65, 66, 66 67. 67, 68. I'm now in 68,

the first year in Mod Sec. Miss [Ruby] Thompson

was the principal. 68, 69 and then 70. 70 is 1970.

So I was able to put in two and a half years in

Mod Sec before I was thrown out of teaching. But

it was such a– It screwed up my head because

I remember one day a friend of mine who had

graduated about a year or so after me. He did

languages. So when I came San Fernando in my

third year of the contract, he was in his first

year of contract and he was teaching in Mod Sec.

He said what we could do lift up these people?

Abandoned and neglected blah blah blah blahblah

blah. He called me, he say Suite, I want to talk

to you. He's younger than me, he graduated after.

He's in English, I'm in Physics and we stood up

talking outside the corridor. And this is a very

important equation in my life because it is what

caused me to move to the next step. And he started

telling me about the children we're teaching and

some of them coming to school with buss up shoes,

all kinds of craziness we have going on in the

school. Of poverty and how some of our students,

they leave there and have no work. Unemployed. I

remember one particular boy from San Fernando. He

ended up winning a scholarship for A-levels. And

he said boy what we could do, what we could do

other than just teaching and we try. Brader and

them was giving lessons to students lunchtime,

in the evening, in chemistry. I was there teaching

some of these students in the evening. Babwah

was staying there on Saturdays to come and play

cricket because he wanted that team to beat QRC ,

amm Naparima where he taught and was a student.

That kind of passion. We wanted to make a— I

dunno, maybe I was being influenced. [laughter]

Seduced. So me and Wayne started to talk–

AA: This is Wayne Davis?

WS: Wayne Davis. He ended up a

vagrant in San Fernando you know. And died. Died

a vagrant. Having been expelled from teaching,

all as a result of that. So we decided look

what we could do? And Wayne said listen we

could organize— I think he was involved

in Tapia. This kind of– [interruption]

I’m just making sure that this

is— He was involved in Tapia?

I suspect he was a member of Tapia and he wanted

to do something like that. The grassroots kind

of education. I tell him I'm not just having

an education class for poor people children,

unemployed. I think but anyhow— And he

organized by a fellow named Sonowa. Sonowa

father had a drugstore near the library,

not too far from here. And Sonowa went to

Naps [Naparima College] just like Wayne

Davis went to Naps. Sonowa stayed to mind

his father's drugstore but Wayne went on a

scholarship to Mona about two years after me.

So we decided, he tell me that Sonowa have a place

up Coffee Street, let us meet with some of the

unemployed youth in the area and see what we

could do because he's not sure what we should do

or could do or whatever. I tell him alright. And

I came down to this, I think I came with a friend

of mine from Princes Town and a cousin of mine to

go and have talks with Wayne off the school campus

about what we could do as young Trinidadians

for the unemployed youth in south Trinidad.

And we had, the first day we had a debate.

Some of them wanted to put on plays,

you know pseudo culture kind of

thing. That was Wayne's position,

he was in San Fernando Arts Council and he

did an English degree so that's how he saw

it. I did physics and I wanted to intervene in the

process of the poverty. In doing something. That

not teaching them simply to appreciate Shakespeare

or [indecipherable] or to read some sophisticated

novel. That is not my— So we had a lot

of debate and disagreement and so on.

And we decided, let us, let us— He knew a couple,

he was from San Fernando, I was from Princes Town.

He will gather some of the fellows, unemployed

youth from San Fernando. And we will start talk

and see what we could do. So I said alright,

I came with my cousin and somebody else from

Princes Town and we went into this building that

Sonowar had on Coffee Street. It was like an inn,

a sophisticated inn where people could sit down

and drink. Educated people. But that was in the

night after seven o'clock of the place

so that it was free for use by us, me and

Wayne and whatever group of whatever call them.

Discards in the society. To see what we could do.

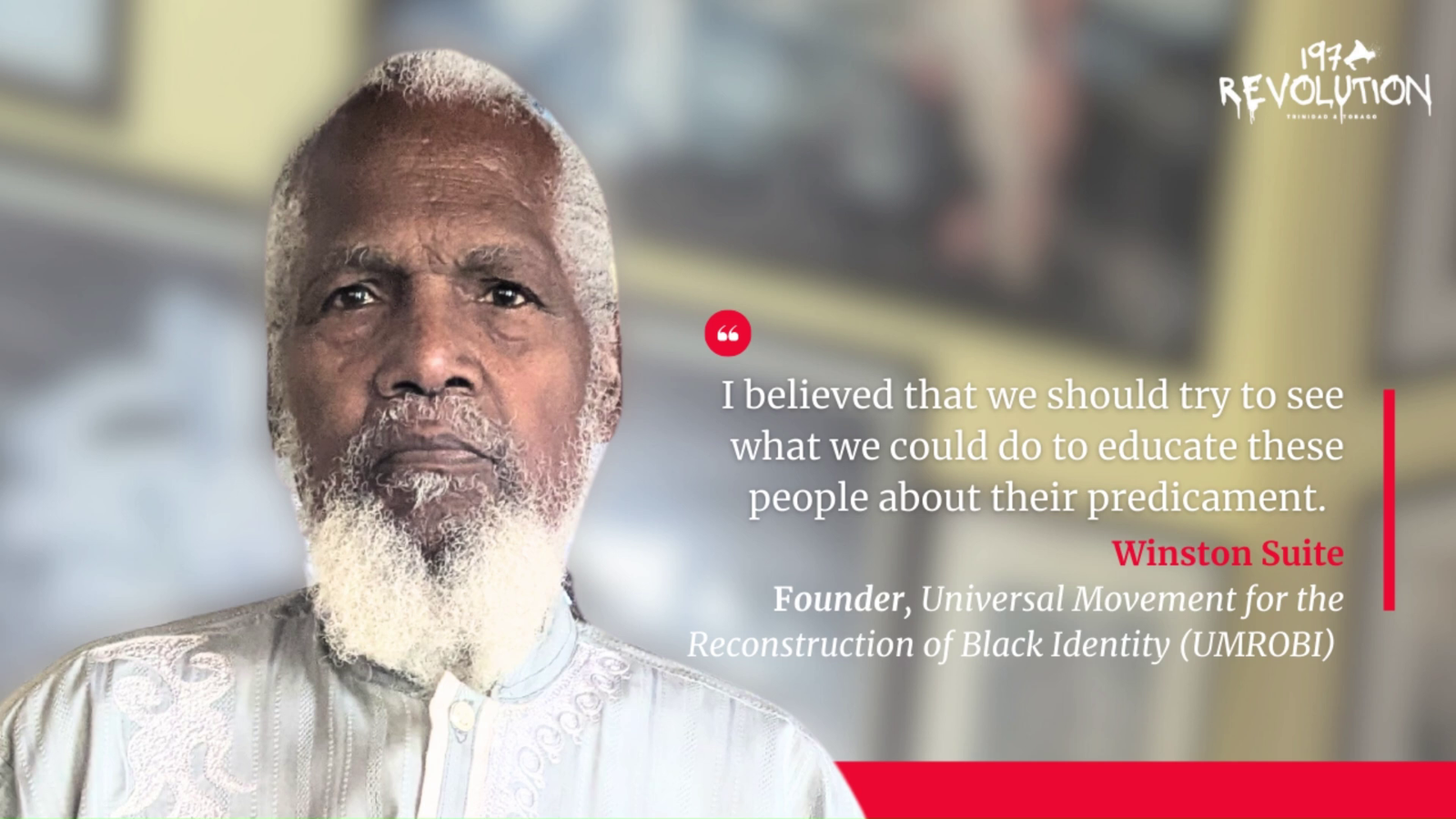

The debate had— We had a heated debate on the

question of– I believed that we should try to

see what we could do to educate these people

about their predicament. At the same time,

see what we could do to guide them in dealing

with the unemployment in whatever way that

came up to make them instruments and agents

of their own. So that important discussion,

talking about the national situation and

we started to meet, we met about three

times. And one night we went in for the

meeting, I coming from Princes Town and

supposed to be there seven o'clock. Eight

o'clock, the door of the place was upstairs,

we had to go up– No Sonowar, no key and we

downstairs. I say, what the hell is this? We don't

own a place. We eh paying rent. And this time

our numbers have increased. About twenty young

men from San Fernando, about four of us from the

Mod Sec, it was mainly Mod Sec teachers in there.

Somebody suggested that there was a fellow called

Jessel Alexis had a rum shop on Cipero Street

and that he liked politics. And that, the person

said they sure Jessel will give us his rum shop,

which is going to be empty most of the time,

to keep our meetings. And we walked down Coffee

Street down Cipero Street into Jessel. I talked

to Jessel, Jessel said is a big place, take it,

go ahead. He had two sons I knew of, one

was in a fifth form around my time He went

to medicine in Howard [University] Then

another older brother, son who was with

one of my brothers in class. So he would

have been four or five years older than me.

So he was– His children, one was away studying

and one in class in Presentation mainly. And he

was one of these activists, kind of interested

in the national politics in San Fernando. Roy

Joseph and politicians of that era.

And we had the whole meeting there.

Jessel said you could come any time, any

time, any day. And I tell him thanks. We

suddenly no longer had to go and stand up and

wait for Jessel, for Sonowar and this thing.

But at the same time, toying with two

things. That while we try to educate

the people in south Trinidad, the young

youth, many of them high school graduates

and some drop out from school. We have to get

them to understand their own predicament. Why

are they unemployed? What could they do about

it? If they have to approach the government,

what agencies they have to approach etc. And at

the same time was the need to evaluate the size

of this problem which became staggering

because every meeting we have— next week

the numbers grew larger and larger, young

fellows from all over the housing schemes

in San Fernando, Marabella, Vistabella and

the border of Mon Repos and all these–.

So we decided that what we need to do

is to make San Fernando aware of the

magnitude of the problem of unemployed

youth and the best way to do that was to

stage a march to put the young people

who are unemployed on the street. To

march from Mon Repos Roundabout through

the streets of San Fernando up on the

promenade. Where we would then allow people

to speak to the gathering and anybody else.

We planned that and that was a early march we

had planned. And we found it coincided when

NJAC [National Joint Action Committee] went in

the church in town, it was the same day. We put

off our march because we felt– and I use the word

‘we’ because we discussed it– that we hadn't done

enough work and that not enough people would

come. And that we do not know the reaction of

the people in San Fernando. We wanted to get the

maximum number and we wanted to be able to– And

therefore the burden of addressing the members

and whoever would turn on— The housing— What am

I saying? The San Fernando Promenade. Harris

Promenade. Very famous in our life later on.

–had the responsibility– It was going to be me and

Wayne and anybody else who wanted to come and go.

So we did that. This would be a Saturday

when I'm not teaching and so we put off

the march because we felt that— So that

is the same day NJAC had their business

done but we had no connection with NJAC.

We were not involved with NJAC. We were

not involved in going UWI [University of the

West Indies] campus, that whole thing. Our

business was south Trinidad and unemployed

youth and what could be done for them.

So how long were you meeting as

a group before you decided to

have the march? The march would have

been– We were meeting, what month–?

February 26 1970 was the day

that they went into the cathedral

1970. Good. We are talking about 69.

About a year or so before that we had

been going on for about a little more than a year.

When did it formally become UMROBI [Universal

Movement for Reconstruction of Black Identity]?

Along the way, I'll tell you about that because as

I said, we wrestled with what is our focus and I

had read a little bit about Marcus Garvey. And

I– how he named his organization the Universal

something. So I patterned the name, I take blame

for it, I patterned the name of UMROBI, Universal

Movement for Reconstruction of Black Identity as

a kind of mirror image of Garvey. Although we were

not saying, we are a Garvey movement but we would

have been influenced by Garvey's original thing.

Then we staged this march in San Fernando. We

went through the streets of San Fernando coming

down up on to the promenade. That

was my first public speaking--

What day was that?

What’s that?

What day was that?

That was Saturday because we have to

teach. My other colleagues have to teach.

So it didn't– It was originally supposed to be

February 26th but it was postponed till when?

I think the week after, or two weeks after.

So that was your first public, major

public speaking moment. How did it go?

We had an Impact on San Fernando.

Because many people came to find out what

that is about, what alyuh–? By this time— I want

to make another statement. We were not the first

in San Fernando to talk about unemployment.

In fact, the first organization to do that

was an organization called Young Power. It was

started by Michael Als, now deceased. Michael

was a brave fellow because he was way ahead

of us. And what he did, he was working on

the unemployment in the oil belt. So he was

catering for Point Fortin, Siparia and he led

a march of unemployed youth even before

us. From Point Fortin to Port of Spain.

When did that march take place?

That march took place before all this

thing with NJAC and even us. Michael,

after he organized that, went to England I don't

know whether he was thinking of studying or what.

But he went to England and, I don't know what

happened, and he came back to Trinidad and found

out that we were active. UMROBI was active

and he made contact with me and started to

talk and he started to come to our meetings.

Michael Als and one of his, his lieutenants,

a fellow called something Mascal. I do not know

his— I look in all those— I don't have anybody

to tell me what was his first name. Just Mascal.

He was living in the Roy Joseph scheme. He used

to have a– he a dougla fella, I remember vividly,

he had long hair up to the shoulders. The only man

who could tell me what was his other name has

since died himself. Another fellow who joined

our organization called Shelton. Shelton

Williams. He died about three years ago

That's what I tell you, most of all, so many

people of that era have died including NJAC. So

our focus was in fact, we were unaware of NJAC and

their business. Because they were operating out of

UWI and they had some links with OWTU [Oilfield

Workers Trade Union] and George Weekes and what

do you call the boss? Joe Young and his– So they

formed NJAC, university students, OWTU and that.

In fact, as we were developing, every

time we go and ask George and them to give

us room to hold a meeting, they gave us a cock

and bull story. I say alright, we will find a

next place. So we had to be drifting around.

I suppose they were more impressed by being

associated with Port of Spain university students.

Who the hell is Suite and these fellows? That

continued for a long time. When we asked them to

give us their hall in San Fernando for meetings,

they used to give us hell, they

wouldn’t– That's another thing. Anyhow.

You were telling me about the day of the march

where you had the first public speaking event

It was important because what happens is a lot of

people were influenced because they saw that this

is not six people. We had people by this time,

we had attracted people from Pleasantville,

that housing scheme area, all the housing

schemes in San Fernando, including Marabella

and Vistabella. We had members joining and I

remember every meeting we had, we used to have

meetings in the night, in one of the housing

schemes that gradually people from-- Older people.

There were two Muslim boys I can't remember the

name because they had an organization affiliated

with Black Muslims in America. But-- What do you

call it again? Elijah Muhammad, that whole thing.

They were Black Muslims in those days, good. This

is before Abu Bakr and all those Black Muslims

and but they didn't have an active organization.

They had one or two members and therefore they

started to come to our meetings. They could get

new ideas, they get more, some people to discuss

with and they understood that they were, they

had fraternal ties with a wider attachment. I

remember those two young fellows. And we started

to attract the unemployed youth. And I would,

a couple of us would go in the various housing

schemes on weekends like Saturday and Sunday.

People would invite you to come and talk to

the block, the scheme. And I would go and

we would talk about all and sundry things.

Where I was learning while I was teaching

and we ended up going, meeting some people from

deep south including some of them who were with

Michael Als before Michael organization was no

longer functioning so they literally come to us.

We didn't have any formal membership form or

officers. We didn't have that structure put--

And that was a serious price for us. We existed

in isolation. We had no contact with NJAC,

I point out to that. We would go and spend

Saturdays and or Sundays in Point Fortin,

where people invite you to come and talk. Or

one of the housing schemes started to increase

your catchment. Princes Town where I came from.

All of Marabella, Vistabella, that whole area up

to Claxton Bay and San Fernando.

That was our focus. South Trinidad.

When the issue about Sir George Williams and that

thing, this is when the NJAC became aware that

there was an organization in San Fernando called

UMROBI. NJAC became aware of that. We didn't have

a very pleasant relationship because they felt

that they were in the news and they were in the

papers. Who the hell is these fellas down there.

Worst of all, George Weekes and them joined NJAC,

had almost nothing to do with us. We had

to pay to use their hall to have a meeting

and this kind of thing but we continued. When

Sir George Williams thing blew up further and

some of them were coming to Trinidad and

[Eric] Williams say he go pay the money

to the Canadian people. They threw out students

for what the students did do blah blah blah. So,

at this point NJAC increased its mobilization

in the north. They would go to Tobago. But

what was interesting is that when they

had their big meetings in the square,

some of our members even I myself would

go to meetings. But I must jump backwards.

Before that, one of our meetings that

we had in San Fernando that could start

sometime Mon Repos or high up in Coffee Street

and then go straight on to the promenade where

we talked to a larger and larger gathering. And

the meeting decided, I say meeting because some

of the young fellows decide, they come and

tell me look man-- we up on the promenade,

that they feel that we should go down High

Street and come back up High Street. I might

have been naive or foolish because our march had

stopped on the promenade and we had had a big

meeting addressing people, not only the unemployed

gathering. And I honestly didn't read the play, I

always admit that. Because it was unnecessary to

go down the rest of the promenade, to go down to

the bottom of High Street, and to come up High

Street which was night. No business places were

open. I misread the play. I always said so. I

paid for it. That's not the important point.

I didn't want to do that. In fact, I’ll

tell you something. When I reached the

top of Cipero Street, Wayne tells me he's not

feeling well or some such thing so. That he

can't go down with the demonstration further

down by Cipero across by Presentation up on

the promenade. Tell me he can't make it

he's tired. Or some other cock and bull.

I said Wayne you're leaving me alone to

be in charge of this demonstration going

down to close off on the promenade.

He said, he said I can't make it,

I’m tired. He wasn't a big muscular fella, he

had a slim frame. I assumed he was a—anyhow.

When we went on the promenade, we had a

meeting. A number of us addressed the crowd and

then we agreed to disperse. Some of the

fellows come and tell me, well listen,

they want to take the demonstration down

to the hospital down the hill and up the

thing. At that point so they will disperse by

the library corner. I didn't want to say no,

I said alright. When we reached the bottom of High

Street, I was in the front of the demonstration,

technically leading the demonstration. We

had some flags and a lot of people in the

demonstration. I remember hearing some loud

noises. I couldn't understand what is that?

Some people said the police behind us at the

bottom of High Street. But I said for what?

And then we realized yes there were police

down there but as some of the fellows had

started to pelt bottle into the showcases of

the business place at the bottom of High Street.

I said Winston, you are screwed. Can't find

Wayne nowhere. Cuz I know Wayne tell meh he

can’t go and I said alright Wayne, alright. At

that point, the demonstration scattered up High

Street. People running left, right, and center

but generally going up. So I was in the front of

the demonstration so I continued and somebody tell

me that it have police at the top of High Street

going to lock up people. They are out

there. So, somebody tell me Suite,

don’t go up High Street. You have to branch

off High Street to a side road. And I took

off before the top of High Street to one of

the side streets where they have shacks. A lot

of shanty. Almost at the top of High Street. And

the police were at the top of High Street locking

up people. On the bottom of High Street police

locking up people. And demonstration disperse.

And I decided-- I remember a woman in one of the

shanties tell me come inside here, come, come,

police locking up people. And I went in her shack

and she asked me where you want to go, where you

going now? You can’t go out there. I said alright

I will go Curepe because my brother was working in

WASA [Water and Sewage Authority]. Was an engineer

in WASA and was living up the hill of Curepe and

she tell me look you hold on here I will get a

taxi for you. And the woman left, went by the

taxi stand by Point-a-Pierre road there. She tell

me when she get the taxi ready, full, one more,

she will come back for me. And I went and sit down

in the woman house. In her shack. And she went and

when the taxi was almost full she sent back her

son or grandson to tell me come it's safe now.

And I took myself up in the taxi stand

opposite what used to be a gas station

and they dropped me in town. They dropped me

in Curepe. Went by my brother and I stayed by

there. Next morning they-- it make Evening News

the next day “Suite at Large”. They lock up A,

B and C. And charge all of us with malicious

damage to showcases and taking part in a riot.

And that was an interesting exercise because it

was the start of my own suspension as a teacher.

This is what appeared, “Top Black

Power Men Held and More Hunted”.

[indicates a newspaper clipping] This is Wayne.

This is [Winston] Leonard. He was with OWTU. They

were not involved. This was just-- I just showing

you a picture of me then. And this is Wayne.

So you disappeared the day after the march.

Yeah. This is [shows newspaper

clipping]. No, that is not the one.

That is not the one. This

would have been in April 21st

So, there was this thing “Suite is at Large.”

Do you have a copy of that one?

I'm trying to—If I find it, I will show you.

So at that point in time UMROBI’s

leadership was just you and Wayne Davis.

We were the main leaders. It had other

people involved-- [indecipherable]

Who else?

Rawle Aimey and some other--

But what was the, can you give a rough

estimate as to the number of your membership?

That's another interesting question. Because of

the very nature of the-- There

wasn't a club with membership.

I see. People would just show up?

Yes, and therefore organizational structure-wise,

we were not well-structured. It was mass

education. That was the focus. It

was not forming a lodge. We had no

membership rules. We had no registration. It

was free. People like me and Wayne and others

giving their service to educate Black people

in the area. We had no structure in a sense.

So you believe that the guys who told

you to carry the march down High Street--

I think he dead. I think he dead now.

You think they did that as a

way to hide their activities--

They wanted to go and mash up-- They must have

thought about breaking up some glass case.

You mean like they specifically had--

I work out up this after.

Yeah, of course. Do you think

that it was just a simple,

like they just wanted to loot?

Or was it that they targeted—

No, no looting took place, it was just--

Destruction of property?

Destruction of this. Because nobody noticing

them or the unemployed. And this

is the unemployed strike back.

I see. But it wasn't like they targeted

specific businesses. It seemed random.

No, they're coming up High Street

and they mashing up people thing.

But the joke is--

So who was arrested? What was the joke?

Well, hear. I disappeared. I explained to you how

I disappeared with the aid of one of these women.

Did you ever find out her name?

Never. I knew the people in that

area. I thought I was doing--

So you took the escape artist route up to Curepe.

What's that?

You took an escape artist route up to Curepe.

Hide in some woman's house and jump in a taxi.

From there, from the opposite, from the library

corner straight in a taxi to Curepe

corner and from there I went up--

And then the next day you see “Suite at Large”.

Well when I reached my brother's house, he

said boy if the police looking, they're going,

they'll come there. And I remember he carrying

me on campus. I was a student long before at Mona

and I was no longer, I wasn’t a student here.

And in talking, he said boy somebody said they

know Clifton de Couteau, who became a Minister.

Also from Princes Town. In fact, he was a student

of mine when I was teaching at St. Stephen’s, he

was a young—Your question was-- If you come here,

the police might come here. So somebody suggested

boy why you don't go on campus and spend the night

by Clifton. Students’ campus, one of

them. And somebody took me and carried

me on campus and I spent the night there.

Next morning, I come back by my brother.

The problem at that point is-- I'm

going to jump back to something--

But the – this is where things, let me

take it slowly--Let me see if I can get it.

Basil Davis was another important moment

in this. Because Basil Davis was shot in

the [Woodford] Square. By this time, I -- The

government had sent me a letter next morning

put me on suspension. Me and Wayne for taking

part in a riot and breaking glass case. Suite

break this glass case and Davis break that

one. The police come and say-- I say what the

hell is this? They say yes, a police man say he

saw you do this. I get away from a jail like that.

By the skin of your teeth!

I had a mission. I had a mission. Cause if I

had come up High Street, anything could ha--.

They charged me for taking part in a riot.

This is how I get put on suspension. The

glass case cost fifteen hundred dollars so I was

charged for malicious damage of a glass case and

taking part in a riot. And this, these, those

two cases were to drag on three, four years.

Let's see if you can get it chronology correct.

So, these protests in Port of Spain by Student

Guild and members of the union was

February 26th. You, UMROBI postponed

their protests until the following week, so

that would have been the early part of March.

Yeah.

And so that's the protest where that riot

took place. Then, the day after that protest,

you said that you went to your

brother's house. The following day,

there was a publication saying, “Suite

at Large”. So, early March, right?

What happened is that Basil

Davis was killed in the Square.

That was in April, right? April? April 6th

Basil Davis-- I had been in town for a

demonstration. By that time, I was suspended--

You were suspended already? Okay. So,

you were staying at your brother's

house all that time? Sorry, you

were staying up north on campus?

No, I had just spent the night there.

I went by my brother's house. But,

the funeral of Basil Davis, there was a

demonstration because he was being buried in

San Juan. So, I had left my brother's house and

afterwards, going to San Juan for the funeral.

While it is, while there, somebody told

me that you’re on the Evening News. So,

I didn’t go to the cemetery for the big 100,000

thing, I just turned back and get in a car and

I went back to Curepe. I went by my brother. So,

I was charged before that because of the riot on

the High Street. And this was what suspended me.

I was suspended from teaching based on those two

charges. Where a policeman named Brayton

from Princes Town was the chief witness

giving evidence that he saw me. He was to be

a chief witness in another charge later on.

I had come out and-- I told you I was in the

Square, I saw the shooting [of Basil Davis]?

Can you tell me more about that?

Yes. A lot of people congregated in the

Square and you had people running up

and down and moving up and down in the

Square. And this fellow, Basil Davis,

and I remember he and another fellow who I

didn't know, they were from Port of Spain was

running out of the Square towards the southwestern

corner. That is the corner towards the cathedral--

And the library.

Right. And I was not too far from there.

But I was in the Square and saw he and

the other boys all walking around in the

Square. And then, I took no notice of him,

I didn't know him. They were waiting for,

I suppose, Geddes [Granger] or somebody

else to give a speech. I had gone to something.

There was a big meeting proposed in the town, I

went to the town. When I went

back, I heard that the police

was looking for Suite. And I took off and

disperse, had gotten away from there--

Tell me about the day at Woodford

Square when you saw Basil Davis.

I wrote something about that. You see it become

vague in your mind. That was

1970, that is how many years?

It's also very traumatizing, isn't it?

Very. Because I saw the fellow

shot. I was not far from here to

the wall [indicated distance].

And this policeman had a gun--

Less than five feet, yeah?

The wall--

Yeah

More than--

This wall, here?

No, no, the glass [indicates distance again].

He is running, the policeman behind him

and the policeman, I remember seeing this stocky

policeman, aiming at him as he exited the back

gate. That gate was open. As he exited there, he

turned left to go towards east and the policeman

is behind him and I don't know-- I think he turned

and the policeman shot at him. But what I vividly

remember in my ears, I'm not familiar with guns,

all I hear is something go bang, bang, bang. With

a highly, not explosive, boom, boom. A light

thing. And the policeman had-- If I am lying,

I could fall right now-- The policeman had

his gun, he had a little gun in his hand

like this [shows size using his hand] So part

of his fingers would have been on the muzzle,

which is short and the rest of the

gun here. And he shot at the fellow.

And this boy, who was, what you call kixsing

around, I don't know what he did to provoke or

vex the policeman. But the policeman was running

him down and he ran through the back gate and he

turned. The policeman shot him and you hear about

two shots and he turned and fall. Dropped right

down the road. So I thought that he kixsing as I

say, that is all part of the whole--That he must

be high on drugs or high on-- well, it wasn't

so much drugs in those days-- high on alcohol.

And as he fell, some people went towards him,

turned him over and when they turned him over,

what I was near enough to see a speck on

his clothes. His jersey open up so and a

speck of blood, because it was not a hole,

I am not familiar with guns, but to me,

it was a speck of blood. And as he dropped on

the ground and turned over, I say he kixsing.

I didn't put two and two together and say, well,

the police shoot him, but you hear the noise,

the police come up and tell people, get

away from here. The fellow is on the

ground and some of the people say, but

the man get shot! And the people coming

to help him because some realize that he is

seriously wounded. In his chest. Left side.

And I had never seen this, I had never seen a man

get shot before. I have not been involved, I am a

school teacher, I am not involved in this kind of

thing. We didn't come out for that. And somebody

say, well, get a car and somebody say, call

a car and they lift him up and put him in the

car to rush him to the hospital. Later on,

we hear that Basil Davis died and that those

shots were shots in his heart. The first time

I was so close to the shooting of a person.

I'm a school teacher. I'm a university graduate

and this and that. I say boy, what the hell is

this? You understand this? Anyhow, that was the

death of Basil Davis. It became a big issue.

He was young, right?

He was a young fella. He was in his 20s. Good

I would have been—19-- 29. He would have been,

possibly, younger than me. And I say, he's one of

the many young unemployed fellows from the Port

of Spain side, congregating in the square, and

the police must be thing him and he running from

the police. And part of it is kixsing and part of

it-- And the first time I ever saw somebody shot.

And killed.

And killed. So this became a big issue. And when

I reached my-- I'm trying to get back things--

When I reached--It is this, I went to Curepe,

not Curepe, San Juan to go to the funeral.

The funeral took place on April 9th, so

just a couple days after he were shot

Yeah and somebody tell me the

papers have “Suite at Large”

Did you know that the police was looking for you?

I suspected that.

Yeah, this is the State of Emergency [indicating

newspaper clipping] I'm going to-- My sister had

gotten this in an old newspaper. I go try

to see if I can find out before you go.

How far did you get? Because

I know the funeral started--

They say, I coming from the east. I

reached San Juan with the thing coming

and people say that the other side

of the funeral was by the overpass.

They were coming up from Port

of Spain to go up Saddle Road--

From San Juan

San Juan, yeah?

Yeah

So you didn't make it very far up?

I reached the junction.

The Croisee.

The Croisee. And I take off. Good? So

that was that. I am now on suspension

You and Wayne Davis. Did you speak to Wayne

Davis after the protest, the riot in Sando?

No, no, he--

He went home.

Yes

Right, and then you said--

In fact, I have said that Wayne was never on the

promenade. I don't know if he changed his mind.

By the top of the Cipero Street, Wayne came to

me and told me, listen, I don't think I can make

it, I'm tired. Just by this funeral agency on

one side of the Cipero. I said to myself, Wayne,

you're going to leave me alone with these men to

see about this thing, man. He tell me, boy, I'm

tired and so on I half believe him, I half didn’t.

But time came when I made the point. To the best

of my memory, I remember standing up and seeing

Wayne going across. It's about three streets,

right? Going back by where this funeral agency

is there. Behind. And I said to myself, this

bitch, [[laughter] this man is going to leave

me alone. Anyhow, frig that. Because I went

back with the demonstration I said, Winston

you can’t duck out. If he want to duck out

that's his business. Well later on, this will

come up because they charged Wayne for being

in that riot. And Wayne's father was a

big man in charge of WASA at the time--

And there were police witnesses.

--and they couldn't save him from getting this

charge or being suspended from teaching and

losing his job and becoming a vagrant. Going mad

and becoming a vagrant in San Fernando. One day

somebody came, by the time I working up in UWI.

Somebody called me and they say “Suite, when last

you see Wayne?” I said, quite some time, I don’t

go to San Fernando. I think I'm now on staff in

the UWI. They tell me, Wayne is a vagrant in

San Fernando, you know. I said, what do you

mean? They said, Wayne's sleeping on the road. You

have to come down south to see Wayne sleeping on

the pavement in San Fernando. That's where Wayne

reached. He paid the ultimate price because of the

suspension. What I did, I decided I was not going

to sit down. I knew that they were not going to

reinstate me. So I decided, Winston, what are

you going to do? You have to start planning.

When I was put on suspension, I didn't

know what the hell I was going to do,

I was still thinking it out. Then,

when the State of Emergency came,

I realized that you ent getting back in

no teaching job. And when I was inside,

I wrote a letter to Ken Julien, if I could come

and register to do a degree in engineering.

That's when you were detained?

During the State of Emergency--

While I was detained.

You decided to become a student?

WS: Because I said I'm not going to sit down on

my ass and let these people screw me. Because I'm

not getting no teaching job, I'm on suspension. In

fact I was chosen, as some people does say. What

happened is, when they suspended me from teaching,

I set a national record. I was on suspension from

April, from February, when this riot took place,

1970, until June of 1965. I was on suspension--

85? You're going backwards.

Huh?

You're going backwards.

How?

You said 1970.

1975.

75. Okay.

And I'm going to tell you why, because by that

time I had done a bachelor's degree in engineering

and a PhD in engineering.

So what's the record? Longest suspension?

Check it. I was reinstated when the

government decided to no longer charge,

carry on the charges against me. The main

charges, the two charge on High Street, I won it.

Okay.

I fight my case myself.

I represent myself in court. And I'll tell you

why, and my wife had nothing to do with that.

And you didn't study law.

--She was in law sometime after. So—

What--

Just now, let me give you this—See

why I say it's good that you come

because next year I mightn’t

be able to remember anything.

I’m sure you will be remembering

for a very long time.

What I said is look, Winston, when they put,

when Williams declared a State of Emergency,

they arrested a lot of us, I included. Put

me on Nelson Island, I spent, I think 28

days of the first State of Emergency. And then

Williams-- They moved me-- I missed the number,

I used to say 17 but some people tell me it's

12 of us who were charged with sedition. I

could call some of them, I tried to call [Clive]

Nunez to get some of the names of the fellas. A

lot of them dead. You see what happened is a

hundred people were detained on Nelson Island.

A hundred people?

A hundred. When I was in the National

Trust, I tried to make up a list and

if you go on Nelson Island, you'll see

a list of names. I did that when I was

now employed as the Chairman of the Board of

the National Trust. That's why I say I would

like to see that place called [Uriah]

Butler’s Island, because he spent more

time there than all of us. He was detained

twice. Good. And you have to document this.

I’ll do my best.

He has to be recognized, he's one of

our national heroes. I know you, I hope,

you have other things to do. But I taking your

time. You're busy? You have to go anywhere else?

I'm here for as long as I need to be here.

Well good. I'm going to tell you all I remember.

Can you tell me what prompted you to

go into Port of Spain for the march?

I went to the march because I’m on suspension

by this time. A big, they're having this big

demonstration in Port of Spain. So I, I ent

working so I said I'm going in town. I'm going to

see, hear what they have to say, what NJAC had to

say. And what is the state of what going on. Good?

Remember at this point, I have two charges against

me. Malicious damage to the tune of fifteen

hundred dollars and taking part in-- Malicious

damage and taking part in a riot. Two charges.

Then Williams declares a State of Emergency on

the 21st. I am in my mother's house. We had a

meeting in San Fernando. And I came home

in my mother's house where I was living.

And we were ole talking, a couple of us

on the pavement. Me and one of the fellows

that I know, who is dead now. And somebody

else. We were there talking and I said boy

it's two o'clock, it's time to go and sleep.

And I went inside in my bed in my mother house.

And then suddenly, she come in the back and

tell me police outside and they come for you.

My mother in a state. In front of my mother's

house, parked up, several police vehicles full

of police men and at the back of the house, in

case I flee or attempt to flee, they had big long

guns. By this time now, so I'm going to find out

this when I come outside. Because when they come,

they come to the front door knocking. A little old

house, my mother, my father there. Police come,

they come. “The big man in San Fernando send us

to bring you down.” For what? They tell me they

don't know, they just given instructions to go and

collect me and bring me down and charge me. And

that was the truth, you know. The police men

who come, they didn’t know what was going on.

They didn't know it was a State of Emergency?

No, they didn't know that. They found out after.

But they were told to go and hold people. And I

was one of the first people in San Fernando to

be held. When I hear, I told my mother, my mother

she said boy the police outside. I tell her

don't worry yourself. Don't worry yourself,

whatever is to be will be. Take off—change my

clothes and I went outside. When I reach out,

they tell me go in the backseat. Police men on one

side and I in the center, and then policemen in

the front. Then I seeing police coming from all in

the back of my house, loaded with big long guns.

In other words, I realise, these fellas surround

the house, they had gone all down in the back,

in the bush, around the house, in case I had

tried to run, they would shoot. I realise

that when I come outside and I seeing police

all in the back of the house and the yard.

They carry me to San Fernando. In the charge

room. The main charge thing, office in front.

And they tell me how the big man-- I'm trying

to remember what the hell was his name-- send

them to bring me. When they bring me, they put me

to sit down in the charge room. They tell me hold

on there and now, I say what am I here for?

They tell me the boss will come just now. It

was four o'clock in the morning when they took

me from my mother’s house. And I never saw a

senior policeman to tell me anything until about

eight o'clock, nine o'clock. I am sitting down,

seeing people coming. They walking,

then they bring George Weekes come and

they put George Weekes there and Winston Leonard

come. Nuevo Diaz. Three fellows who was walking in

the union. Senior officers in the

union. They put that-- They don't

seem to know what was going on. One of them

start to suspect, boy is a State of Emergency.

I was the first person to be brought in from

Princes Town. The others came in after and

somewhere around eight o'clock,

nine o'clock, or something so. They

come and usher you in downstairs, into the Black

Maria, you know the big van that they do thing,

inside, lock the door. And you inside.

Nobody ent telling you anything,

explaining or telling. They don't have

no responsibility. They say that they

get instructions from Port of Spain to go and

collect the rest of you. All right, that was it.

I don't know, whether they will—in those

days, the government could have shoot you.

They could have claimed to say you get shot in

anything and-- When you reach Port of Spain,

they decided to head towards St James to the

army. And when they reached the army gate,

I remember this vividly, that's why it's

important that you-- Nobody waiting for you to go?

When I am, I reach Tetron. And I said nobody

know the hell... All of we. Four of us,

five of us. Nuevo Diaz. George Weekes. Winston

Leonard. In the back of the van. And they drive

in. They reached to go into the-- What do you

call it? The base. Nobody know what happening.

I remember vividly looking out through the wire

up, high up there and I saw a young man who I knew

in my youth. He came from Princes Town, we used to

call him Balcatee. His name was Harold Stephens,

right. Years after I saw him in Sea Lots. He used

to live there but we never got to meet to talk

about that. I saw him there and I said boy what is

going on. He say boy, hell going on in the army,

the army revolt. I say alright. That’s all he

know. And he is now on the outside of the gate

with some other military people. This is a friend

who grow up with me, he about a year older than

me. He used to live in a house about from here

to a lil further than that one [points] next

door. We grow up together. Balcatee. Sister name

Ingrid or Evelyn, something so. I remember his

brother name Joseph. All ah we grow up

on the same hill in Princes Town. Nobody

could tell you what happening. They

took me in to town. When you reach

down on the base and you hear that they in thing

here. So somebody in the gate vicinity tell them,

you better carry those fellas back

in town because the army in upheaval.

This is the same day that

Raffique Shah and [Rex] Lasalle--

They were inside the base with their

own problems inside of there, which

I knew nothing about. I had never met Raffique

Shah, I didn't know Raffique Shah. I had never

had any dealings with any of the fellas in the

army. They carried us back in to Port of Spain,

in the main police station. You see the

one that Abu Bakr and them had blow up

once? Carried us downstairs. They have big

cells downstairs, and they put you in a cell,

I can't remember whether I was alone or what. What

I remember vividly is that we could climb up and

peep outside at the highest level and realize

that, what you are seeing is the road level,

so that your building in which you are,

you are in the basement, below road level.

We stayed there for quite some time until it was

almost dark and then they came back and they moved

us from there back into a van, back down in

the base. And when we come out of the base,

this fella, [Jack] Kelshall, the one who, was

he the one who had the [indecipherable]? It was

either him or his brother or his cousin,

I can't remember who it was. But Kelshall,

one of them, was in charge of a set of Coast Guard

people and they took us out, put us on a boat,

and carried us out to Nelson Island. Come out

and you went. They had, what do you call it,

police? Coast Guard. Coast Guard and

some police surrounding the building.

The building is still there if you go and get

a, excuse me, a view of it. And they put us

inside the building. The building had no rooms.

Subsequently, they went and they built cells, but

then it was one big open hall, and they locked the

front door on us and that's it. So that now, this

is night of William's State of Emergency. By this

time, you find out there is a State of Emergency.

But while we were downstairs in this basement,

you're hearing people running up and down.

Police running up and down. Because

some of them are frightened, they jump

in their car and they going because they're

afraid of the army. And every now and again,

you hear some gun shoot off, because, and

you are now eight feet below ground level,

kept in this darkness, in a literally at the

mercy of whoever, whatever, on whatever charges.

I spent 25 or 28 days, one of those numbers there,

on Nelson Island. By which time, they had more,

almost 100 people collected down there.

Then we were taken into Port of Spain by

[indecipherable] into the Red House. Driving from

the basement of the Red House, coming inside,

and you're come up the stairs, that was the

high court. And we were read charges. That

you were charged with sedition. Somehow

or the other, I think we knew that we

were going to court. They may have read

the charges on Nelson Island for us. And

I remember writing a piece of prose, I

wish I find it, I can't find it nowhere.

At that time, you wrote this thing?

Yes, you expect to die anytime. I wrote,

it was in defense—[phone chimes] I'll

call the name just now. There is

a French Jew who was charged with

sedition and he spent time on an island, on

the island. [Captain Alfred] Dreyfus. I tell

you, I'm frightened [points at head].

I hope you taking all this down.

[laughter] You're doing a good job.

Eh?

You're doing a good job. Don’t worry

about your memory, it will come.

I wrote that, because, to me-- I used to

read a lot-- Dreyfus was charged because

the other non-Jewish officers were envious of his

meteoric time in the French-- And they conspired

to fabricate a charge of treason against Dreyfus.

It's a famous, books have been written on it. And

films have been made on it. And the case has

been about, you know-- because Dreyfus, somebody,

one of the famous French philosophers organized

a mobilization of people in France, in Paris.

And forced them after a couple of years to open

the case of Dreyfus. And Dreyfus was exonerated.

So you felt this was similar to your situation?

Because some people had fabricated a charge

against him. Because I’m saying, what have I done?

But sedition is supposed to be proven, isn't it?

Well, girl, all of those things.

So about 100 people would

have been charged for that?

No, they were charged with

lesser things. About 12 or 16

of us were charged with sedition.

And that charge would be vacated,

six and some years after. The government

one day, by this time I finish the masters,

the bachelor’s degree. I had almost finished

the experimental work and the write-up

of the first draft for my PhD. And I received

a letter while I am finishing my write-up.

It was telling me that the government was

no longer intending to pursue the matter of

sedition against me. And therefore, I had

to report to the Ministry of Education to

be reinstated in my teaching job. So I was

on suspension with half pay, that's a next

issue I’ll raise today. Wonderful story. I was

charged with sedition with twelve other people.

On the 23rd of January, February, I was put

on suspension until- that is 1970, 1976, June!

I received a letter. By which time, I had done

a bachelor's degree, I got a first-class. I did,

I got a scholarship to do my PhD, I get vex

then, so I decided-- Just the same week when

I got vex with them, I was on a research-- What

do you call it again? A fellowship, scholarship,

government, university scholarship for coming

first in your class. That's another story.

There were people who were trying

to stop me from getting a job. And

I said, really, if that is the

case, if I come first in my class,

and alyuh doh want to give me a job, and

I see you hiring other people the years

before. Hiring people who ent do as good, I

think, I said, no, I got mad vex and I said,

it's a good thing I had been working pell mell. I

said, decided on my own, I was not-- I finished--

I did the master's, the bachelor's degree

but it cost me four years because after

I finished the first year, and going to

second year in November, the government

extended the State of Emergency, and

locked me up the second time. So,

I was suspended in all-- First,

we spent from April to November

April to November. The first State of Emergency

The first State of Emergency. Then

the second State of Emergency,

it was about nine months. So in all,

it was about 15 to 16 months in prison.

In the prison.

The second time-- therefore I lost a

year. I end up doing the degree in four

years, that I should have done in three years.

And while I was in there, I said, I'm not going

to waste my time at all. And I decided that I will

set my own pace. I will finish my PhD. This is

not arrogance. This is-- I was screwed, and I had

to catch up. So I decided I will not spend three

years, I told my potential supervisor, he told

me to come back and do a master's. I said, if I

come back and do a master's, maximum two

years. I will finish this in two years.

All I want is your support, and to make sure

that they correct it on time, and two years.

If it's a PhD, three years. I'm not staying

any-- I have lost too many years. Good? So,

I told you, the government decided

after six years and something,

six years and a half, that they will no

longer pursue that case. In the meantime,

I had defended myself on the two charges

in San Fernando and had them thrown out.

I appeared on my own defence. So, it took me about

three years for the case to come up, and every

day I had to take time off from my lectures and

to go down to San Fernando. I was mad vex. And

there's no stopping me. When you're mad vex, you

do all kinds of things, you know. I

was mad vex. I was mad vex for years.

If you weren’t suspended-- I would be mad vex too.

I finished my PhD, experimental

work, in a year and a half.

Really?

And when they told me that in June, I had almost

written up the first draft. And I said to myself,

I said, Winston, these people testing me. And

I go in the Ministry, and I remember the fellow

who I had to meet. I tell him, I say, why are you

all sending me Point Fortin as a relief teacher?

You're all trying to get me to resign. And he

smiled and smiled and said, is that possible?

He said that?

I said, anything possible. And I said, never

forget it, I decided I will go-- Conveniently,

I got annoyed with the university because

they didn't want to appoint me on a job.

Somebody make me apply, and when the

time comes, they had they meeting,

and they said, well, no Suite don't have enough

experience. So they're not giving me-- Yeah,

I don't have enough experience. And they did

not want to—A certain fella in the faculty,

senior in the department didn’t want

me. I wasn't the right kind of person

And I was to show them that I'm more

than the right kind of person. So,

I resigned from the teaching fellow,

what do you call, teaching assistant,

instantly that evening. The same evening, I

decided to resign, I get a letter telling me,

report to the Ministry. I said, so

I resigned from the UWI, and I said,

I do, I finished all work. My first reaction was

emotional, was to burn, I'll tell you the truth,

was to burn my thesis. I had all the

experimental work written up in two years.

I said, this stupid thing tries to drive me—all

the years I spend doing that, my bachelors,

my PhD finished, almost. What are they going to

say, that I'm a mad, that I’m incompetent, or what

it is. But the forces were great. The forces

were great that were allayed against me. So,

they sent me to Point Fortin, as a

relief teacher. I did it for about two

weeks. Leave Tunapuna where I was living to

reach San Fernando, racing hard, and one day,

I'll tell you the truth, this is undocumented,

one day I overtook a taxi driver, round a corner,

and as I overtook the driver, something came

to me, Winston what the ass you trying to do?

You're going to get killed. Possibly that's what

they wanted to do, by sending you down Point. So,

you know what happened? End of June, I resigned.

So, I resigned from teaching, and I pack up. I

changed my mind, I said, alright, I won't

burn the thesis. I almost finished it.

[laughter] Good!

Because my aim was three years. I had it done,

inside and out. But the forces allayed against

me. They take long to correct it. So, it ended

up three and a half years, before I graduated.

I said, well, the forces that are against you,

are not equal to the forces that are for you.

I left teaching, the longest person on suspension,

six years and a half, or something like that.

And then, they threw up their hand, and

they're no longer charging sedition against

me. I won the cases in San Fernando. I had a

PhD, I had a master's degree. I said, well,

what the hell are you doing? My brother told me,

he had an engineering company, he said,

well, come and work. I didn't want to work--

I went and worked for him for

six years, as a contractor.

After that time, I was tired of that, and I left.

And, at that time, they called me in the faculty.

If I'll change my mind and come and work. I said,

yes and, I went back to the university after six

years And, I have never left. Because, when

I left, I was kept on for about three years,

part-time. And then, Julien called me to join

the staff at UTT [University of Trinidad and

Tobago]. I stayed there for about 15 years,

or 18 years, or something, helping them do

their work. I'm still a professor emeritus in

UWI. They appointed me a professor emeritus.

So, I say the forces-- For some reason,

they wanted to teach me a lesson or just

set me on a path of wanting-- But, I

didn't want to be a teacher. But, so

here am I, being a perpetual student.

And, a reluctant teacher.

No, I'm not a reluctant teacher.

Not anymore?

No. My students, in a way, make me feel that I

have done wonders. I never wanted to be a teacher.

But, when students meet me in the airport, or

they meet me, I just came back from the UK and,

they come and look for me. And, carry on this kind

of thing to make me feel good that I help them,

I said, well, boy, possibly you

didn't want to be a teacher, but--

You were meant to be a teacher.

--But, you had to be a teacher. That is not your

choice. I resisted the idea of being a teacher.

I thought that that was not what I wanted.

So, what did you think you wanted to do?

Medicine. But, that is another story. That you

might have to save-- Ask me

what you want to ask me now.

So, the two charges during the State of

Emergency were both sedition charges?

The two charges, no, first I told you the two

charges before the State of Emergency were--

Yeah, those two were--

It was based on the High Street thing,

right? Malicious damage of breaking a

glass case and taking part in a riot.

Yeah

Those were the two charges.

Right. And then, for State of Emergency,

you were charged with sedition both times?

But, there was only one time. You were

charged with sedition and they just keep--

And they extended—Right, okay.

I wasn't studying them. So, at the end of

it, I said-- some people say you're blessed,

others say you've had a function, a

role, something to play. And that's,

that is why you were protected. You

are protected. I told you my age?

Yeah.

I tell myself, I am lucky. There are

plenty of people who grow up with me, dead.

There are plenty of people who are

detained with me, dead. So I say, well,

boy, possibly somebody watching over you and you

have a purpose. It's arrogance, eh? Sounds like

arrogance. But I can’t explain it. I mean, when

the struggle going on, you feel bitter and when

it finishes, you tell yourself, it could

have gone on--. You know, Wayne became mad.

But he wasn't--Was he also arrested

during the State of Emergency?

Yes. Well, he was kept on Nelson Island. When he

came out, he was already shaking from the impact

of the thing. And then, after that, Wayne became

mad. Lost. Became insane on that, whatever you

call it. So I say, well, boy, you could have

been like that. There are a lot of people who,

when they went into their lock up, they just

give up. Some of them didn’t know what to do.

Some migrate. One or two of them who migrate were

able to finish—[Russel] Andalcio was able to do

a degree somewhere in Canada. So that all have

not failed. Some of them were able to establish—

There's a fellow, a Jamaican fellow, [Carl]

Blackwood. He was, detained with us and

charged us with sedition. He ended up with a,

going to France and England, I think. The last

time I heard about him is that he was in Canada.

He did a PhD in electrical engineering. He was

doing electrical engineering, bachelor's degree

here. He ended up doing a PhD. So he did fairly

well after. He got married to an Indian girl,

her father had an engineering company here. So,

the story is about that.

What other areas are you interested in? As I

told you, I went back in the UWI, I became an

academic. I had my struggles with them inside

of me. They found that I want to go too fast.

What, what became of UMROBI?

That's a nice question. When I came out of

prison, the first time, we assembled, reassembled.

Decimated. And a lot of people frightened

and all kind of things. Some were in prison,

someone in detention, some afraid that-- the

police threaten them and all kinds of things

like that. It was an elaborate program to

destroy any kind of organizational thing. All

the organizations in general, they suffer from all

different kinds of problems. We had the harassment

of the police and young people feel afraid and

then the government started the programs here

and there. And they will give out something here

to distract the young people. It was difficult.

So what we did, we joined, there was

a No Vote campaign. We got involved

with [James] Millette and their organization and

a few other organizations and we organized the No

Vote campaign. That was when I came out. So I

spent my time studying academic work and doing

political work. That was all I stopped reading

anything, never go to-- stop going to the cinema,

stopped doing this, stopped doing all that. I

devoted my life to two things, the organization

and getting a good degree. And then, that was

then, the second State of Emergency, locked up

again. And we came outside and reorganized with

great difficulty and after somewhere around--

I'm trying to remember the

exact time-- this is about 1976.

We had joined-- Raffique Shah

joined with [Basdeo] Panday.

Panday and they had the-- what

do you call the organization?

I'll call it-- this is Panday and Shah, Joe

Young. I'll call it-- They had an organization

and that survived and we used to, some of our

members-- we had a long debate what we should

do and some of them decided they want to get

involved in that and a couple of them went

into that. And we kept surviving, meeting

from time to time. Diminished. Depleted

number and impact. Then we started to face

reality in 1976. ULF [United Labour Front]. Some

of our members tried to be in

ULF and be in our organization.

And the strain became too great for people.

We were all six years older, who had wife and

children. And the question of jobs, difficulty

in getting jobs. You can't get jobs with profile.

We engaging in

a serious analysis, a serious

analysis as to what is demanded

from the members by the objective

situation in politics and decided

one day that--you end up with the shell

of an organization. NJAC went through the

same kind of thing. We decided we would close

down shop. It was a sad bitter day and we did

that for a number of years, members shut

down but kept active. Some members went in

the trade union movement, others retreat

and then go away. My own personal case,

I decided that there are other

ways to contribute to this.

I took up the issue of writing, I hope

you would be interested in some of this,

I took up the issue of reparations. I have written

possible a dozen papers. Some of them published,

some of them not published. About what reparation

means, what do we expect of our so-called national

leaders. But first thing, I broke up the

whole historical period into looking at the

issue of the African man in the Caribbean, as